Dear Jen,

I just found Bullish/TheGloss and want to say thank you. I also want to say that when I read you were/are(?) a bodybuilder it made me that much more excited!

I’ve recently discovered weightlifting and want it to actually matter. Thank you for saying it’s okay (and GOOD) to lift heavy things.This is where my question lies. The gym I have access to is an all women’s gym. As such, we have the teeny free weights. Dumbbells are 20 lbs. at their heaviest, and barbells are in 10 lb. increments at the heaviest without an Olympic bar (the bar seems like carbon or some other light metal).

Do you have suggestions for working with this set-up? There is a new machine circuit, but from my understanding free weights are best.

Ideas? Advice?

Great question!

First, check out Bullish Life: Gentlewomen Don’t Crash Diet if you haven’t already. (For anyone wondering where unicorns come in, here.)

I haven’t been working out for the past couple of years, but I’m actually going to dive back in, with all the before-and-after pics and everything. It’s something I could never forget how to do. Like a much more complicated version of riding a bike.

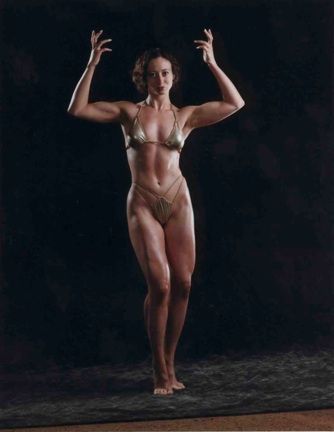

Also, the biceps never really go away. This is me in college (I had NO IDEA how you’re supposed to pose, so I know I look dumb. Impressively dumb, but dumb.):

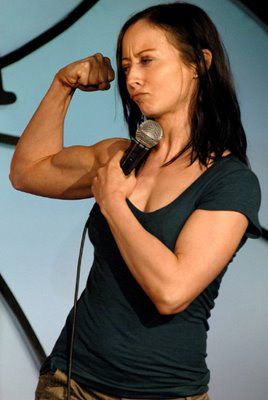

And this is me doing standup comedy years later:

Not only do the biceps stick around (they look normal when I’m not flexing them; I have small lady-arms), but one of the main benefits of weightlifting for me was vastly improved posture. I was a slumpy teenager. People would tell me to sit up straight, but it was like I wasn’t even able to. Six months of building back muscles, and I had the posture of a Greek god.

This article is going to be in two parts: What To Do About Your Lady-Gym, and Lessons From Weightlifting That Also Apply to Life in General. So, those of you who aren’t interested in the first part, please do move along to the second.

What To Do About Your Lady-Gym

Here’s the thing — yes, free weights are “better.” But for a beginner, it doesn’t matter much. This is true in many fields: the fine details and the very latest developments matter only to people already at the top. I’m sure Tiger Woods has very strong opinions about his golf clubs, but I think you could spend your first couple years of golf practice using basically any kind of golf clubs and you’d make huge improvements.

Generally, free weights are considered better because:

1) Your muscles are activated at every point in the motion, whereas on machines there are parts of the motion that are suspiciously easy (which you don’t want).

2) When using free weights, you have to develop coordination, and control of small muscles that help to control the weights. (If you watch someone bench press for the first time, they usually can’t keep the bar symmetrical at all).

On point (1), this is actually not necessarily true anymore. I mean, it was true of weight machines in the 1970s, but advances in the design of these machines has in some cases actually made the machines better. For instance, consider a shoulder press machine. An old-school shoulder press machine was pretty simple – you press straight up.

When you use this machine, the top part of the motion often feels easier than the lower parts of the motion. Whereas, with free weights, you would squeeze up towards the top (make the dumbbells touch over your head), making that part as hard or harder than the rest.

On a newer shoulder press machine, the arms may function independently, and are curved so that when you are in the fully flexed position (arms up, shoulders almost locked, but never actually locked), you’re squeezing your deltoids together. This is a good machine.

If the machine you have is old-school, you just want to control your use of it — if the final part of the motion is too easy, don’t go up quite that high. Stop extending your arms at the point where holding up the weight is very difficult; pause; slowly lower. Skip those last two inches where your muscles are actually getting a break.

I also think there are a few movements where machines are better because free weights are super-awkward or impossible. For instance, the seated row machine. You CAN’T do this with free-weights (because: gravity). A bent-over row is a substitute, but seems to stress my lower back and exhaust my grip strength way before my rhomboids even get involved. So I LOVE the machine.

There are plenty of other motions where bodybuilders’ large muscles just kind of outpace their wrist or grip strength, which is why they sometimes use wrist straps when using barbells. You don’t have to worry about this for some years, or maybe ever, but I’m just saying — the people who design machines know about this stuff and endeavor to fix it. Many modern weight machines were created in direct response to the notion that “free weights are better than machines.”

On point (2), this coordination stuff is nice, but it’s probably not why you’re working out. It won’t change your appearance, general health, etc.

Finally, machines are a GREAT way to develop good form when you’re starting out. It’s kind of hard to use the wrong muscle group to complete a movement.

So, what I would do if I were you:

Spend 6-18 months at this little lady gym totally maxxing out everything they have. Use all the machines.*

(*Not the stupid inner/outer thigh one. A bunch of ladies always line up for that fucker, thinking it’ll make their thighs look good. NO. It only exercises the muscles that MOVE your thighs. Thigh muscles are quads; you exercise them with squats and lunges and the leg press machine. Look up any picture of thigh muscle anatomy — that dumb inner/outer thigh machine mainly works that little twisty muscle that looks like a thin diagonal strip. There are valid sports and health reasons you might care about this, but this machine is likely to have little, if any, effect on your appearance.)

To get the most out of the tiny free weights, lift with super-strict form, and very slowly. You’re trying to make the movement harder, not easier. Think: just how much muscle fiber can I break down with these 15 lb. dumbbells? Because that’s actually what you’re trying to do.

Unless you are freakishly strong already, you can do pretty well with those little weights for awhile. (On upper body day, if there’s any doubt, finish off with some pushups and just make sure everything’s exhausted.)

Also: side delts? With this exercise, 5 lb. weights are plenty for most people. If you can do side delts with 15′s, I’d bet money that you’re not doing it right.

Then, while you’re maxxing out the resources of this tiny lady-gym, figure out a plan to get access to a big gym in a year or so. That’s plenty of time to work something out. Think of the big gym as a reward for totally owning that little lady-gym.

Also, if you want to see something amazing, rent the documentary Pumping Iron II: The Women, a battle for the heart and soul of women’s bodybuilding, in which the super-butch, 10-times-more-muscly Bev Francis is accused of “ruining” the sport of bodybuilding by being too good at it, while the conventionally-hot, skinny Rachel McLish frets that “the hair is just as important as the muscles.” Who wins? SUSPENSE.

Lessons From Weightlifting That Also Apply to Life in General

When I was talking about how to better use machines, I suggesting omitting the “easy” last few inches of a movement. How do you know when you’re doing this correctly? Well, the right muscle group is activated the entire time. And by “activated,” I mean a progression from “Neat, I can feel that!” to “Fuck, I feel as though I am birthing a baby through my quadriceps.”

This idea that you choose your own response to pain — here is a lesson for the rest of life. One that bodybuilding allowed me to feel viscerally. When you are lifting weights, you are actually aiming for a slow, steady, healthy feeling of muscle pain. But it’s not bad pain. It’s like the burn you get from your mouthwash. You know it’s killing bacteria, so you feel pretty good about the hot-and-tingly sensation. It’s a healthy, productive, controlled pain. LIKE SO MUCH ELSE IN LIFE.

Most people do not have enough body awareness to distinguish between “pain” and “inability to continue.” (METAPHOR ALERT.) They are not the same thing. When lifting weights, the last few reps are supposed to burn. (Stabbing pains, asymmetrical pains, and joint pains are not good; this is different.) Your body has been trained to recoil from pain; you put your hand on a hot stove and remove it without thinking; you lift something at the limits of your ability and immediately stop because it hurts. However: it’s just pain. Pain doesn’t stop you from continuing.

When you kill that knee-jerk reflex to respond to pain by quitting, and instead realize that you actually have the power to keep going, well … that’s one superhero fucking feeling. And true of so much else. Animals have an automatic pain-avoidance reflex; self-aware humans can analyze the costs and benefits and decide to push forward.

Please enjoy lifting heavy things, should you choose to do so! Either way, at least now you know about the inner-outer thigh machine.